If you're white, you're all right.

If you're brown, hang around.

If you're black, jump back.

--children's rhyme

If you are unprepared to encounter interpretations that you might find objectionable, please do not proceed further. --Harvard University Implicit Bias Test Introduction

I was a tornado of a little girl. I had lots of energy and imagination. I made up songs and dramas and acted them out --by myself if no one was around or wanted to play with me.

I loved the social life of elementary school and the intellectual challenge. I can't remember not knowing how to read. I loved nap time in kindergarden. I loved cookies for jobs completed in first grade. I loved my second grade teacher's turban and long arm of bracelets. She was light brown and bought me a notebook.

I did not like being Black. I did not like my dark brown skin color. I did not like the jokes, the criticisms, and the presumption that I was not pretty because I was "dark-skinned."

"Don't turn off the lights; we'll never find Amanda!" would always get a laugh.

I wasn't good at put-downs so I would smile and pretend I did not care. I felt guilty as charged. I was Black. I didn't know of any insults for being brown, tan, yellow, coffee colored, etc.

I grew up in the 1970s in a predominantly Black neighborhood with a sizable Puerto Rican and Latino population. It was still an insult to call someone "black." I remember someone saying: "I'm not Black; I'm brown."

Yes, this was the time of James Brown's "Say it Loud, I'm Black and I'm Proud," but it was also the time of only lighter-skinned women being featured as Jet Magazine's Beauty of the Week.

All of the new Black television shows and movies of the 1970s featured women who were lighter skinned --unless they were playing asexual, mammy characters. Think "Julia" or even "Raisin in the Sun."

To comfort me, my foster mother would say "Don't you worry, baby; you're getting lighter every day." I was the only dark brown girl in the family. I hoped she was right because the only other dark brown person in the house was my foster brother, a teen who was always in trouble.

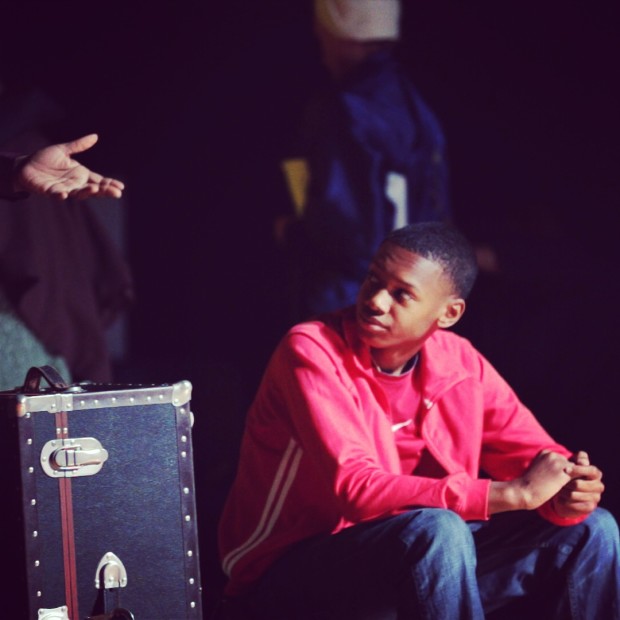

Eventually, I started fighting back. In junior high, a group of boys would pick a girl they thought was ugly and scream at her in the hallway while we changed classes. I'd watched them do it to several girls--all dark brown. I was in the smart class. I had glasses. I had crooked teeth. And, most importantly I was Black.

When they screamed at me, I just kept walking as if I didn't see them. I don't know if my friends were with me, but I felt alone.

One of the boys stepped in front of me and said something, and I opened my mouth:

"You're no dreamboat yourself" came out.

I kept walking.

All of his friends laughed. They were shocked an "ugly girl" had hit back. They were shocked at my word choice. I know because they said so.

Later, when I was in my final year of junior high, a boy shouted as I passed by "you look like an African queen."

Now in my neighborhood, even if we had mostly gotten to the point of not denying we were black, we were emphatically NOT African. Notwithstanding the Black nationalists, the Nation of Islam, and other folks countering the narrative of Africa as a dark continent, most people in my world did not respect, value or claim any connection to Africa.

Therefore when he put 'African" in front of queen; I heard it as mockery.

My response: "That's the best kind."

I tell you these stories because I've battled to see my skin color as sensual, rich, and one of my best features. I have fought despair and loneliness when I was passed over because I was too dark. When I read about dark brown women characters choosing navy and brown clothes so as not to draw attention to our skin, and I went out and bought yellows, reds, pinks, and white.

After I graduated from college, I was approached by my friend Luis, a light-skinned Mexican American. I tried to explain my hesitance to date him. I liked him. A lot. He was really cute and artistic. But, I said, very gently "I'm really Black." I'll never forget his reaction. He literally fell down on the hiking trail in laughter. I tried again: I am not a "by the way" Black person. (I love this story and promise to write another post about what happened after that.)

I am now almost fifty. Studies show that colorism and white supremacy persist, but I resist. I have degrees and certifications in African & Afro-American Studies and African Studies. I've taught Africana Studies, classes on whiteness, and post-colonialism. I've lived on the Continent, organized Black students, represented Black community interests, and organized in support of African liberation movements. I've built an identity around actively fighting for Black Art, Black complexity, Black traditions, Black intellectual history.

I had battled and lost. My unconscious, the realm out of my control, had learned "If you black, jump back."

I did not like my results. Yes, I had grown up in a white supremacist society. Yes, I'd gotten messages my entire life, all around me every day that light is better than dark; white is better than black; etc.

It's understandable, but still, I do not like my results.

Immediately questions rise:

My children: one brown, one tan. Do I prefer the tan child?

My stepchildren: two blondes, one brunette. Do I prefer the blondes?

My husband: blue green eyes, grey-white hair, white skin. Do I prefer white men?

I do not like these questions.

If you're white, you're all right.

If you're brown, hang around.

If you're black, jump back.

But I sit with them.

I commit again to find and declare the Good, Beautiful, Powerful, Smart, and Lovely in Blackness, in dark-brown people.

I challenge you. I invite you. Take at least one action every day for a week to counter the implicit bias to favor light-skinned or degrade dark-skinned people. At the end of the week, join me for a conference call to share what you experienced. If you can't make the call, write something somewhere. Here's a study with some suggested actions. Email me for the conference call details.

Peace and love,

Amanda